Laos is many things: an impoverished country ravaged by American bombs and unexploded ordnances, a jungle paradise, and a travel destination for tourists looking to escape the beaten path.

We took a short flight from Hanoi to Luang Prabang, the “cultural capital” of Laos, and one of Laos’ two UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Monks in bright orange robes carry woven baskets and walk in pairs from the market to any one of hundreds of golden temples, or wats. The sun, a shimmering red and purple blaze, sets over the sleepy waters of the Mekong River, on which long, colorful boats await curious tourists.

Luang Prabang is home to a fantastic labyrinth of a night market, complete with covered street food vendors and Laotians selling baggy pants, art scrolls, and coffee, among a sea of other things. When we were shopping, dripping sweat underneath red and blue awnings, haggling with every vendor we encountered, it was hard to maintain any sense of direction. This likely contributed to me buying altogether too many gifts.

Southeast Asia, and Laos in particular, has challenged the relationship I have with my stomach. As per usual, I want to eat everything. Street vendors rarely disappoint. Cumin, chile, coriander, onion, coconut – the medley of flavors and aromas, walking down nearly every street, is intoxicating. Unfortunately, I had my first bout of real sickness in Luang Prabang. As is healthy for any set of travelers, this provided Sara and me the opportunity to spend some time alone. While my beautiful, adventurous friend explored waterfalls, I huddled under a mosquito net in our room, attempting to stomach both the food from the day prior and a strange Japanese novel I was reading, called South of the Border, West of the Sun. I didn’t realize that the protagonist, a middle-aged Japanese man suffering a mid-life crisis, is entirely self-involved until the end of the novel. I suppose one of the themes, in addition to the tendency of people to constantly live in fear of the “what if,” is the essential egotism of humans. The book was powerful and disturbing. But I was thankful that it took my mind away from the delicious and potentially disastrous foods surrounding me.

On one of our sunny days in Luang Prabang, Sara and I rented bicycles and set off in search of a waterfall. We rode through small Laotian villages outside of town, passing children walking home from school, venders selling watermelon and mango, shining wats with golden Buddhas beckoning, and clothing lines with monk robes hanging to dry.

After riding on a bumpy, unpaved road for a few kilometers, we realized that the waterfall might have to wait for another day. Somewhere off of the jungle-lined path, we discovered an oasis of a spot, which turned out to be a cooking school called Tamarind. I was busy trying to figure out what a Tamarind is, envisioning a kind of monkey that lives in the area. Thinking that maybe we might be able to buy a delicious Laotian iced coffee, we walked through palm fronds and past sleeping dogs to a kitchen, where we met Halan. Halan works at the cooking school, and was positively thrilled that we chose his workplace to rest. He offered us a tamarind. As I was preparing myself to ensure that whatever monkey coming my way did not have rabies, he brought out a rough, brown pod about five inches in length.

It tasted like generosity and prunes.

Our next stop in Laos was Phonsavan, a dusty, crumbling town that had an unfinished feel to it. To get there, we crammed ourselves and our luggage into a sweltering minivan with ten other tourists. The minivan climbed jungle-clad mountains, passing groaning buses and resting motorcycle drivers, all the while honking at aloof naked children bathing alongside the road. The drive was picturesque, but demonstrated the immense rural poverty that plagues Laos.

We headed to Phonsavan in order to witness the Plain of Jars, an archaeological phenomenon. Megalithic jars speckle the countryside in Xieng Khouang Province, an area of Laos that is known for its dangerous, potentially explosive fields. Many archaeologists believe the jars are two-thousand-year-old urns, while the Hmong people believe they were used by ancient giants to make rice wine. Sara and I, creative geniuses that we are, made up our own story complete with a queen, three daughters, and a limerick. I’ll spare you the details.

As we viewed the jars, we were instructed to stay between the small, cement markers that line the “safe path,” where Laotians and tourists alike can walk without fear of explosives.

The night before we explored the area, I went to a local bar to watch a movie titled “The CIA’s Secret War in Laos.” I walked into the bar and mentioned the sign outside advertising the movie to the bartender. He grabbed a DVD case and directed me to a small room in the back, with a black and white TV and a dirt floor. I watched the hour-long movie with an open mind. The director of the movie, and many of its participants, were Americans, all of whom discussed the incredibly detrimental effect Americans have had on the geographic and political landscape of Laos. According to the movie, when Vietnam War pilots could not hit their targets in Vietnam, many dropped their bombs on Laos without questioning the consequences. As Kennedy and Johnson publicly recognized Laos’ neutrality during the war, fear of communism and the “domino effect” provided American politicians enough impetus to arm the Hmong people to fight the communists within their own country. The Hmong people, a generation of young men and women, were obliterated.

While we were in Phonsavan, we visited a Hmong village. I was nervous that it would be similar to the experience I had on Lake Titicaca, when I visited the island of the “native” people, all of whom seemed to present an artificial preservation of culture to please eager tourists. Thankfully, the Hmong village seemed untouched. Sara, our tour guide (Mr. Wong), and I walked around a small village, complete with cows, a monkey, wooden buildings with thatched roofs, and pigeon coops supported by bomb shells. The surreptitious presence of bomb shells, as building supports and flower “boxes,” was disturbing.

Poppies are one of the primary sources of income for the villagers, reminding me of the heroin drug addictions suffered by locals and American soldiers alike during the Vietnam War. We were welcomed into the home of So, a young Hmong man who kindly poured us shots of rice wine and practiced his English. As we were sitting around his small hut, on thatched stools, I realized how fortunate Sara and I were to be offered such an opportunity. Graciousness, even among great poverty.

Phonsavan was a strange, decrepit place. We were glad to take another winding, scenic bus ride to Vang Vieng, a small town in the south known for its antiquated party culture. In the past fifteen years, tubing down the Nam Song River became a tourist endeavor and unfortunately, a wild party attraction. Fed up with pulling an overdosed tourist from the river once every ten days, the government shut down the bars alongside the river in an attempt to quell the madness in Vang Vieng. The locals in Vang Vieng were, to put it mildly, cold to us. Who can blame them? Only last year, loud Westerners smoked weed on the streets, wearing nothing but bathing suits, disrespecting Laotian culture and the peace that encapsulates so much of Southeast Asia.

We decided to observe the social environment, be as respectful as possible, and not take anything personally. There is something artificial about the place; at night, restaurants play Friends or Family Guy on big screen TVs, while tourists sit comotose on beds and eat. Sara loves Friends, so we watched a few episodes. But mostly, I looked around and thought about the stale energy of the place. Vang Vieng is a very different place indoors than out.

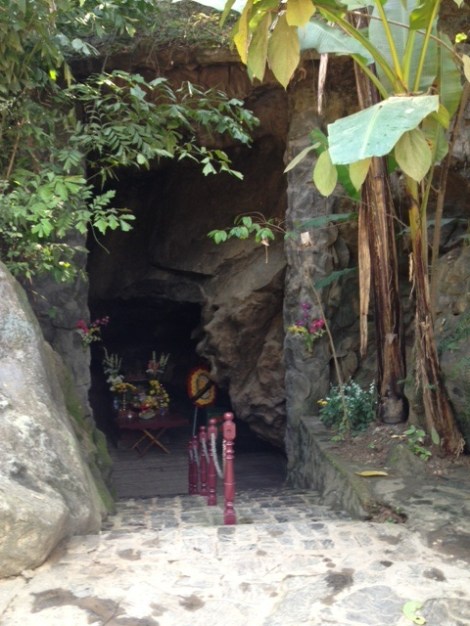

During our three days in Vang Vieng, Sara and I tubed down the river, marveling at the limestone rock faces and jungle walls lining our path. We biked down dirt roads, much to the chagrin of our butt muscles, passing cows and local people, to a cave. We leaped into rivers from sprawling treetops, swam with fish, and drank coconut milk. We made friends. We thought about how lucky we are. We realized how important education is, and how many rural people in Laos never receive the opportunity to go to school.

See that smile? It keeps on going. We are headed from Chiang Mai, Thailand to Bangkok tonight on a bus. I don’t have an iPad to lose this time, so I’ll focus on my latest novel: Roberto Bolano’s 2666. And when I arrive, I’ll be directing all of my energy into singing this, as many times as possible.